Detecting Phishing Emails with NLP and AI

Update: I uploaded the code to GitHub. You can find it here.

For this post, I am discussing a project I undertook to solve a ubiquitous issue in cybersecurity: phishing. Realistically, my efforts can not equal what large corporations have already achieved. I do not have their resources or expertise. Thus, my true aim is to develop a solution using publicly accessible data (in addition to emails from my personal inbox) and code which can run on my laptop.

In concrete terms, my aim is binary classification of phishing emails, where the “true” class contains phishing emails, and the “false” class contains benign, non-phishing emails. The only information considered for classification is the body text of the emails. This makes the project simpler from the outset, since I used multiple datasets which had differing formats. Additionally, it makes the classification models developed more general as they can be applied to any text, whether it be a phishing email, website, or social media post. Applying the models to other mediums is outside of the scope of this post; however, I may write about this topic in the future.

The project I am describing in this post is by no means rigorous research. I am not an expert in AI or data science; This is merely acting as a hobby project. Considering that, my methods are unscientific and should be regarded as a preliminary exploration into the topic of phishing classification.

Datasets

One problem I identified in previous research is a shortage of data. Many papers used a singular, small dataset which I believe may have led to overfitting. If one, for example, only used a dataset of emails sent and received within a single institution, say a company, there would be a high concentration of text referencing the company. Emails from another company would be unlikely to contain the same topics, which may cause classification to be more inaccurate. To reconcile this, I used as many phishing email datasets that I could find publicly. The datasets are Nazario phishing corpus, Clair fraudulent email corpus, and the Spamassassin corpus. For benign (non-phishing) emails, I used a combination of three large datasets: the same Spamassassin corpus (easy and hard ham), the Enron email dataset, and finally a portion of my personal inbox. 4821 of the total emails were phishing and 5303 were benign. The emails were split using sklearn’s train_test_split with test size of 0.2, resulting in 8099 training emails and 2025 test emails.

Preprocessing

After writing code to read all the email body messages, (nltk)[https://www.nltk.org/] and (gensim)[https://radimrehurek.com/gensim/models/ldamodel.html] were used to preprocess the emails. After working with the data for a while, I generated a WordCloud image to easily display common words in the dataset. I then used this to extend nltk’s built-in English stopword list to include common words that were impertinent. A selection of the extended stopwords list is shown below:

stopWords.extend(["nbsp", "font", "sans", "serif", "bold", "arial", "verdana", "helvetica", "http", "https", "www", "html", "enron", ... "margin", "spamassassin"])

I used gensim to strip tags, punctuation, multiple whitespaces, and digits. Furthermore, words shorter than 3 characters were stripped, and the words were stemmed.

Features

I proceeded by training an LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) model on the total corpus using gensim. This was used to retrieve the top topics for each email. I also used gensim to train a Doc2Vec model on the texts in order to vectorize the body text of each email. Then, sklearn was used to create a TF-IDF vectorizer on the text, and the features were acquired for each email. The sentiment intensity analyzer that is built-in within nltk, VADER, was used to quantify the negativity and positivity of each email. VADER only scores negativity, neutrality, positivity, and “compound,” so future work could be focused on implementing a more complete sentiment analyzer into the codebase. Finally, I created a list of phishing and spam keywords, which I retrieved, funnily enough, from blogs which teach the reader how to avoid being caught by spam filters. This was used to count how many blacklisted words appeared in each email.

A few other features were fetched from the email bodies: whether the email contains HTML, whether any hyperlinks are included, how many words are in all caps in the email, how many exclamation marks appear, the total length in characters of the email, and finally the word length. In summary, the features used for the AI models are:

- The top topics from the LDA model

- Doc2Vec vector

- TF-IDF vector

- VADER Sentiment Intensity Analyzer scores

- Number of blacklisted words

- Whether it contains HTML (true/false)

- How many links are included

- How many words are in all caps

- How many exclamation marks

- Total length in characters

- Total word length As one can imagine, this resulted in a large amount of features for each email.

Models

Now, turning toward the models themselves and the training process, I used sklearn to implement an RFC (Random Forest Classifier) and an SVC (Support Vector Machine Classifier); however, after seeing some of the results of the SVC, I decided to drop the SVC out of consideration entirely.

Importantly, I used tensorflow to create a CNN (convolutional neural network). The CNN used either two or three (this value is one variable tested, see results) 1-dimensional convolution layers (named Conv1D in tensorflow). When testing with two convolutional layers, a dropout rate of 0.5 was used for the first of these layers. When testing with three, the dropout applied to the first two layers. Additionally, a dense layer with “ReLU” activation with a dropout of 0.5 was placed between the last convolutional layer and the output layer. Finally, the model was compiled with the “Adam” optimizer.

As I mentioned above, the number of convolutional layers acted as a variable during testing. The number of filters of output space for each convolutional layer were identical to each other; however, that number, consistent among each of the layers, was varied during testing. This, as well as the other variables tested are discussed in the next session.

Results

The variables tested for this project were:

- The number of topics for the LDA model

- The number of maximum features for the TF-IDF Vectorizer

- The number of filters of output space (output dimensionality) for the convolutional layers in the CNN

- The total number of convolutional layers in the CNN

The first two variables apply to both the RFC and the CNN, while the latter two only affected the CNN. There were, in actuality, two sets of testing data. The first is the testing data mentioned above, which was derived from the test-train split. The second data set was the remainder of my personal inbox which I did not include in the training and testing data. I did this to see if the models could be reasonably applied to an inbox of “real” emails, not just those relegated to public datasets. I also did it simply out of curiosity, but I thought I would share the results anyways. I did not include my full inbox in the original training set to begin with because that would have made the benign emails greatly outnumber the phishing. The resulting accuracy for the first dataset is labeled “Validation Accuracy.” Accuracy for my personal inbox is labeled “Personal Validation Accuracy.”

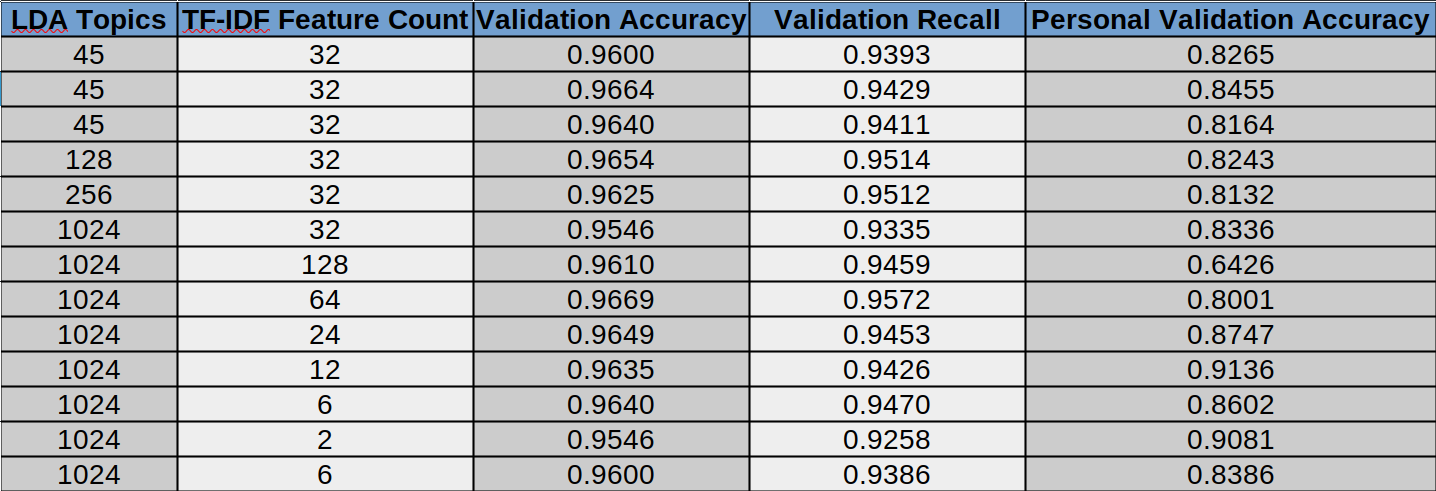

RFC

As shown in the figure above, the validation accuracy did not change much with the variables. Additionally, the validation accuracy on my personal inbox was considerably lower than on the original test dataset. The best combination of variables for validation accuracy was 1024 LDA topics and 64 TF-IDF features, with an accuracy of 96.69%. For my personal inbox, the combination with the highest validation accuracy was 1024 LDA topics and 12 TF-IDF features, at 91.36%.

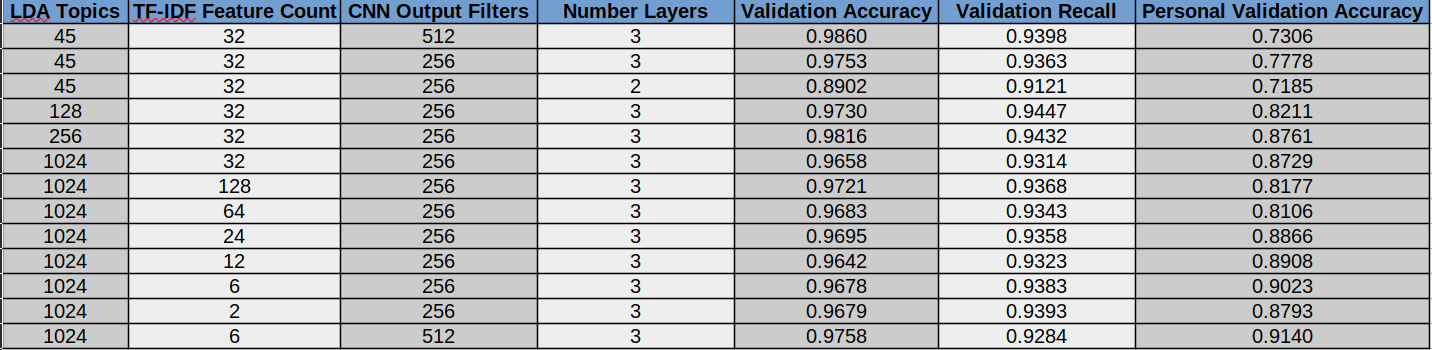

CNN

The validation accuracy for the CNN ranged from 89% to 98.6%. The highest accuracy was found to be 45 LDA topics, 32 TF-IDF topics, 512 output filters, and 3 layers. The validation accuracy for my personal inbox was again much lower than the other testing dataset. The highest accuracy for my inbox resulted from 1024 LDA topics, 6 TF-IDF features, 512 output filters, and 3 layers for the model. This accuracy was 91.4%.

Conclusion and Future Research

Both the RFC model and the CNN achieved impressive accuracy; the scores were 96.69% and 98.6%, respectively. I originally did not intend to use such a large amount of LDA topics. I assumed that a low number of features, anywhere between 2 and 10, would be sufficient. Despite my expectation, after working with the data for a bit, I kept increasing the number and found that the accuracy increased for both models. While more than 1000 topics would certainly provide little benefit to a human in modeling and understanding the corpus of emails, it seemed to provide some value to the models.

The TF-IDF feature count that resulted in the best accuracy was 12 for the RFC and 6 for the CNN. These numbers numbers are quite close to each other and are low compared to the number of topics. Perhaps this indicates there are only a few key terms that are important to phishing classification, however I am doubtful of this conclusion due to the large number of topics.

The combination of 512 output filters and 3 layers resulting in the highest accuracy for the CNN indicates to me that larger models may be better able to classify phishing emails. This conclusion is consistent with the sheer quantity of features being considered for classification.

Unfortunately, it appears that I have concluded this project without solving the issue I introduced at the beginning of the blog post: lack of data. I believe the discrepancy between the validation accuracy for the original test dataset and my personal inbox indicates that the public datasets I used were insufficient. While the validation accuracies for the original test dataset are, I think, quite remarkable for a simple project such as this, the much lower accuracies for my personal inbox are unacceptable. Assuming a 91% accuracy, roughly 1 out of 10 true positives would be missed by the classifier (yes, this is a gross simplification, I am just illustrating my point), which could be disastrous in a real-world, enterprise context if these models were being solely relied on. My guess is that these public datasets don’t represent the large majority of modern phishing (and benign) emails, and that not enough data points were present during training for the model to perform well in the real-world.

All this being said, I believe future work could focus on working with better, larger datasets. This would only be possible for the average Joe like me if large organizations release new datasets for researchers. While this is a complex issue due to possible re-identification (anonymizing email text would be quite difficult), public data would help propel research into this topic. In regards to the models, it appears that CNNs are particularly adept at classifying phishing emails and that the NLP methods used in this blog provide sufficient features to tackle this task. Incorporating the machine learning phishing URL classification methods already present in the literature with body-text analysis of emails would likely be fruitful for future research. Other methods which could be incorporated are the real-time classification of the actual sites that are linked in emails, and the a priori knowledge of the site’s trustworthiness from sources such as VirusTotal. This is already being done by email security products, but public research into this would be valuable.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: